The consul was already old by then.

The consul was already old by then.

That night, as any night, he was having a shower before going to sleep. While soaping himself, he was thinking about his wife Elizabeth: he pictured her smiling, joking with him leaning against the fridge; then he saw his five-year-old son, one Sunday morning, with his latest brand new shoes; then his brother Anthony, serious and still, in black and white, just like in the picture he used to keep in his wallet.

Nevertheless, this last thought was interrupted by something which appeared to the consul like the cry of someone falling. A very slight cry, imperceptible as a whisper.

His glance flew to the flowered shower curtain and drifted down to his feet: he noticed the usual old corn, then he followed the water, to the lather which was running to the whirlpool; it was there, it was in the whirlpool of water and lather, that he saw a really tiny camel who was struggling just for another moment before vanishing in the drainpipe.

The consul rinsed himself well, put on his pyjamas, slippers and went straight to bed. It couldn’t have been anything else than a joke caused by tiredness.

He got into bed already thinking of something else. He read almost two pages of a boring novel and fell asleep without having the time to put the book back on the table nor switch off the lamp.

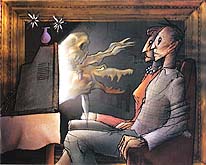

He had bad dreams. In the middle of the night he half woke up. He didn’t open his eyes but noticed anyway that he hadn’t switched off the light. He was trying to find the power to order his half-asleep hand to switch it off when, all of a sudden, realised that there was an indefinable movement around him.

Slowly he restrained his breath, opened his eyes; but closed them almost immediately. With a really light movement he bit inside the cheek to bleeding: he was awake. This time he slightly half-opened only one eyelid: the little camels kept going back and forth on his patterned blanket, on the sheet, on the cushion; kept going in and out of his ears with confidence.

Although his eyelids were almost closed, he could notice that the small animals were all exiting his head with a package between their teeth. He tried hard to convince himself that he was tired, but he couldn’t believe it anymore: the little camels were real. And they were a host. They were passing through his ears carrying stolen packages from his head goodness knows how, and who knows where to. Some shameless little robbers were plundering him in his bed.

The consul got in a fury but could control himself. A buzzing, as of a fly, let him know that a couple of them had stopped just at the entrance of an ear, talking. He focused his attention on that buzzing… he could understand them; he could perfectly distinguish every single word: they were talking about the little camel Markoskintu who had fallen into the drainpipe.

They were really sorry. The consul tried to breathe slowly, always keeping the same rhythm. One little camel asked the other what he was carrying in his package and he answered that he had a good remembrance; he said that he was carrying away the image of Philip and his latest brand new shoes.

They were really sorry. The consul tried to breathe slowly, always keeping the same rhythm. One little camel asked the other what he was carrying in his package and he answered that he had a good remembrance; he said that he was carrying away the image of Philip and his latest brand new shoes.

The consul shuddered, searched his memory for the image of his son Philip with his latest brand new shoes and couldn’t find it. He felt that picture had been his for a long time but, although trying hard, couldn’t find it.

“Let’s go away now,” a little camel whispered, and added: “there is no hurry; we have still two years, seven months and four days.”

They left: one climbed on the cushion with many others, the other one went down on the consul’s still arm; as he reached the hand, this went off like a trap and imprisoned him. A general rush happened.

The little camels were overwhelmed by panic: the ones next to the ears went back inside, vanishing into the head; the others scattered in the bed’s periphery. In a moment everything became really calm in the room.

“What will happen in two years, seven months and four days?” The consul’s voice was dry, as he had run out of saliva. The little camel imprisoned in his hand was confused, but behaved irreprehensibly. Soon he apologized on behalf of all the colleagues for having been caught; then he said that he was really sorry, that such an accident had not happened more than four thousand times in the whole history of humanity, and he could have gone on beating about the bush if the consul, resolutely, hadn’t repeated the question.

The little prisoner was then precise and essential: “In two years, seven months and four days, at twenty-one thirty-six sharp, you shall die.”

The consul didn’t turn a hair, but the little camel realized anyway he had been a bit too brutal. When, after a small pause, he restarted talking, his behaviour was almost tender. He said: “My colleagues and I are the little camels of memory and we carry away the remembrances of dying people.” He talked with a slight foreign accent: “Unfortunately we don’t always succeed in terminating this operation on time. Some people, sometimes really young, die suddenly; some even kill themselves on purpose, and one who commits suicide, as you might know, dies with all his memories. You have been lucky, we have been contacted well in time: we already slowly started to move twenty days ago. In two years, seven months and four days at twenty-one thirty-six sharp you shall die, with few indispensable secondary memories.”

This time the consul’s voice was only tired: “I want to die now, carry away all my memories and let me die immediately.” And added: “Please.” The little camel thought about it and then decided that he would please him. It was the least he could do: “But I must inform you that the heart attack you should die of in two years, seven months and four days cannot, due to the regulations, be precipitated. Thus, you shall die of pure death. It will happen tomorrow night, in this very bed. Death will kill you without dressing it up as illness, nor accident, nor anything else. It won’t give any technical explanations for anyone: it shall be death, and that’s it.”

The consul put his fist on the cushion and opened it: the little camel stretched well his legs and humps; then, trotting slowly, went back into the ear, when he remained just for a short time. An instant later he was already galloping towards the edge of the blanket waving his arm.

The consul put his fist on the cushion and opened it: the little camel stretched well his legs and humps; then, trotting slowly, went back into the ear, when he remained just for a short time. An instant later he was already galloping towards the edge of the blanket waving his arm.

The consul saw his son again, with his latest brand new shoes, and then spent the night remembering.

The morning after he woke up really early and, as usual, went down by the stairs; he always avoided lifts. As he reached the sidewalk, he had to wait in the fresh air for a never-ending lorry to pass; then he crossed the road.

It was a special day. When he took the number-twelve bus, it was already dark. He waited for his stop looking outside the window. As he got home he undressed, had a shower, washed his teeth, put on his pyjamas and went to bed. Unexpectedly, he fell asleep almost immediately.

The little camels didn’t keep him waiting: some came out of his ears, others, really a lot, came goodness knows from where.

They carried away his wife Elizabeth smiling, joking with him leaning against the fridge; his brother Anthony, serious and still, in black and white, just like in the picture he used to keep in the wallet; his five-year-old son, one Sunday morning, with his latest brand new shoes. Then another memory, and another, and yet another. In less than an hour they carried away all his remembrances. The last little camel took away the memory of the little camels.

In the room, once that swarming coming and going ended, everything was quite: you could only hear the consul’s deep breath.

In the room, once that swarming coming and going ended, everything was quite: you could only hear the consul’s deep breath.

After a while, on the limited horizon of the patterned blanket, a little pearl-grey dromedary appeared. In a short time he was over the blanket and lay down on the edge of the sheet; then, with a wild galloping, climbed the cushion and went down on the old man’s shoulder. When, extricating himself among the pyjamas folds, finally reached the chest, stopped, bowed his head and bit deeply, toward the heart, with his ice teeth. At that point, for the consul it was just the end of a dreamless sleep.

Original title: “I cammellini della memoria” from the book “Altrove è l’unico posto possibile” (“Elsewhere is the only possibile place”) by Filippo Martinez, Edizioni del Girasole 1995. The pictures in this page are copyrighted by Filippo Martinez.

English Translation by Raffaello Tesi (2002). Thanks to Ros for the proofreading.